Lavender from a scientific viewpoint

Botanically speaking, lavender is a lamiaceae (formerly called labiate) like other aromatic plants such as thyme, mint, and sage.

The flower houses four stamens (its male components) comprising a narrow part, the filament, and an enlarged part, the anther which contains the pollen. The female part, the pistil, has four dry fruits (grains)at the base of the calyx. The style common to these four carpels or pistils opens at its top to two stigmata which receive the pollen.

The secretion system:

Lavender and lavandin, like other lamiaceae, have cells that contain a very fragrant essential oil.

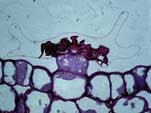

Ovule from a lavender flower

Tests conducted at various stages of growth using electron scanning microscopy have considerably advanced the knowledge of the lavender and lavandin secretory systems.

The calyces of the lavender flower are observed to be arranged in a regular series of mounds and valleys sheltering the essential oil producing structures (or secretory glands).

A thick felt-like protective pile covers the sides.

These spherical epidermal glands have diameters smaller than a tenth of a millimeter. Their activity ensures the synthesis of all the essential oil constituents, and, ultimately, their long-term storage.

How these structures, which are akin to many tiny essential oil factories, function is far from being completely understood. The potential roles played by essential oils could be as the plant’s chemical defense against micro-organisms or as an attractive lure for pollinating insects.

The secretion glands

The secretion glands are distributed throughout the entire plant. Occurring rarely on the upper faces of the leaves and stems, they are somewhat more numerous on the undersides of the leaves but they are especially abundant on the flower’s calyx (sepals).

The secretion glands are distributed throughout the entire plant. Occurring rarely on the upper faces of the leaves and stems, they are somewhat more numerous on the undersides of the leaves but they are especially abundant on the flower’s calyx (sepals).

This tubular calyx appears with longitudinal striated furrows. The secretory cells are grouped in the valleys of the furrows, a thick mat of “hair” trichome braces covering the sides.

With no secretory activity strictly speaking, these branched trichome braces, consisting of several arms, participate in the plant’s water balance, especially the calyx – because they slow the evaporation rate and protect the essential oil production structures.

It is this trichome bracing that gives the plant its “downy” texture. This protective matting exists as well on other parts of xerophytic plants that develop a protective and adaptive system that enables them to survive in dry regions.

The presence of secretory essential oil glands sheltered by a tight network of trichome braces is not peculiar to only lavender and lavandin; other plants, mainly the Lamiaceae, are disposed with the same system: officinal sage, thyme, rosemary, etc.

The production of essential oil – apparently linked to photosynthesis phenomena – is thought to be a plant’s reaction to dryness.

collapse of a receptor gland

Receptor glands

Receptor glands generally comprise eight cells, grouped to form a “head” supported by a large unicellular foot which joins it to the epidermis of the calyx.

The multicellular secretory gland is covered by a “skin” (cuticle). As long as the secretory glands produce essential oil which accumulates under the cuticle lifting it little by little to allow more storage space, as much as double the size of the secretory cells themselves.

Contrary to the widespread belief that the essential oils are liberated by the glands exploding during distillation, the pouch containing the essential oils, emptied of its contents, simply collapses on the secretory cells in the glandular head without tearing up.

* Photos by A. Perrin et M. Colson, Laboratoire Professors at BVPAM, St Etienne University

Source: "Lavandes et Lavandins", Christiane Meunier, Editions Edisud, 1999